Right to Refuse Medical Treatment

All adults with decision-making capacity (i.e. able to make decisions for themselves) have the right to accept or decline medical treatment—even if decisions may result in a poor outcome, including death. This fundamental right to refuse medical treatment is considered a negative right—the right to not be touched and to be free from unwanted medical interventions. Overriding a decisional patient’s refusal is not ethically or legally permissible.

Even adults who lack decision-making capacity retain the fundamental right to refuse recommended treatment. Health care professionals are required to respect their refusals, except in limited circumstances as outlined below.

In ethics terms, treatment given over objection violates the ethical guideline of respect for persons and can only be justified in specific situations.

Decision-Making Capacity Review

Decision-making capacity (i.e. the ability to make one’s own decisions) is a clinical determination that refers to whether a patient has the mental capability to:

- Understand relevant information,

- Appreciate the medical situation they are in and its possible consequences,

- Reason through risks, benefits and alternatives of treatment options, and

- Communicate a choice freely and voluntarily based on their own values.

Only adults with decision-making capacity are able to provide informed consent or an informed refusal.

Adults with Decision-Making Capacity

Having the right to refuse medical treatment does not mean that when a decisional patient says no, that their refusal will be accepted without question. Any time a patient declines a recommended treatment, it means that they and the treating clinician view the situation differently. That is okay. It is not the patient’s job to simply “go along” with what is being recommended. Rather:

- A decisional patient’s job is to consider all the options and decide what is best for them.

- What is most important from the medical point of view may not be most important from the patient’s point of view, because goals and values may differ.

- As long as a decisional patient has been given all the relevant information about their treatment options and knows the risks and benefits of each option, including the risks and benefits of turning down treatment, the patient’s wishes come first and treatment over refusal is prohibited.

Clinicians are obligated to promote the health-related interest of their patients. They do this by making medical recommendations that support restoration of health and well-being. When patients disagree with or refuse those recommendations, it is ethically permissible for clinicians to encourage acceptance of reasonable medical alternatives that align with the patient’s goals and values. This means that clinicians can respectfully persuade their patients to reconsider decisions and explore other appropriate options that align with their goals, but cannot force them to change their mind.

Adults Who Lack Decision-Making Capacity

Adult patients who lack decision-making capacity still retain the right to refuse medical treatment in all but exceptional circumstances. The two circumstances where it is permissible to treat over the objection of an incapacitated patient are:

- If the patient has waived their right to refuse in an advance directive (Ulysses Clause), or

- If the situation would result in serious and irreversible bodily injury or death if the health care is not provided within 24 hours.

These exceptions are defined in Vermont statute, which sets the threshold for when it is permissible to treat a patient who lacks decisional capacity over their refusal: [see 18 VSA §9707 (g)(1)]

(g)(1) Health care shall not be given to or withheld from a principal over the principal’s objection unless:

(A)(i) The principal’s advance directive contains a provision, executed in compliance with subsection (h) of this section, which permits the agent to authorize or withhold health care over the principal’s objection in the event the principal lacks capacity; and

(ii) The agent authorizes providing or withholding the health care; or

(B) The principal lacks capacity, will suffer serious and irreversible bodily injury or death if the health care cannot be provided within 24 hours, and:

(i) the principal does not have an agent or an applicable provision in an advance directive, or the agent is not reasonably available; or

(ii) the agent or advance directive authorizes providing or withholding the health care.

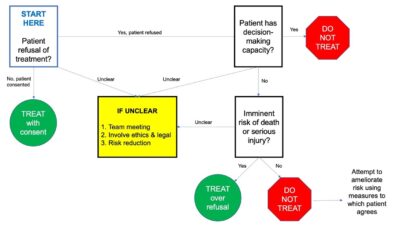

A Helpful Algorithm to Determine if Treatment over Refusal Is Permissible

*Flow diagram used with permission from UVM Medical Center Departments of Clinical Ethics and Legal/Risk

Additional Information about Treatment over Refusal When Patient’s Lack Capacity

Refusals do not need to be verbal. Patients may refuse treatment in a non-verbal ways. Clinicians must be mindful of nonverbal forms of refusal and approach those expressions with caution, so as to minimize intrusions on patient autonomy.

If a patient who lacks capacity refuses medical treatment and there is no imminent threat of serious bodily injury or death within 24 hours, treatment over the patient’s refusal is not permitted unless there is a court-appointed guardian with the power to consent to the treatment [see 14 VSA §3075(g)].

Risk of “serious and irreversible bodily injury or death if the health care is not provided within 24 hours,” is a clinical determination made by the treating clinician. Clinicians must guard against an overly liberal interpretation of imminence so that infringement upon patient autonomy is minimized.

If treatment over objection is provided under the 24-hour statutory provision, the treatment can only continue until the patient has stabilized and the risk is no longer imminent, or the patient is agreeable to ongoing treatment. Once stabilized, if the patient refuses continued treatment, clinicians must respect the refusal. It is ethically impermissible to force treatment on an unwilling patient as an ongoing plan of care.

If a person with mental illness is experiencing a medical emergency and is refusing recommended medical treatment, clinicians will assess their decision-making capacity.

- If the patient has capacity, they have the right to refuse and the refusal must be respected.

- If the patient lacks capacity, the same rules for medical treatment over objection apply. Clinicians must believe that there is an imminent threat of serious bodily injury or death within 24 hours in order to override the refusal. [see 18 VSA §9707 ]

If a person is experiencing a psychiatric emergency, the patient would need to meet the criteria of a person in need of treatment (i.e. suffering from a major mental illness) who, as a result of that psychiatric illness, is at imminent risk of serious harm to self or others under the Rule on Emergency Involuntary Procedures [see 18 VSA §7504, §7505 and §7508].

There are many medical and psychiatric conditions that can pose sufficient threat to patient safety for clinicians to believe it is a “medical emergency”. However, if the emergency does not pose an imminent enough threat to life and limb as defined in Vermont law. (i.e. irreversible bodily injury or death within 24 hours), the patient cannot be treated over their objection regardless of their capacity.